Professor and grad student join together to find answers on climate change’s effect on vegetation

Second-year geography graduate student Sydney Bailey is working with Professor Grant Elliott, leading the reins on a study using tree rings to reconstruct seedling regeneration at the upper tree-lines in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado. Their goal is to see the effect of climate change on seedlings and note how vegetation interactions have shifted over time.

They sampled vegetation at six sites on three mountain peaks: one peak northeast of Santa Fe and one north of Taos Ski Valley in New Mexico and another peak south of La Veta, Colorado. Bailey and Elliott, along with the another biogeography graduate student, Steve Cardinal, spent three weeks hiking and studying these sites during late July and early August. Their summer field season was pushed back nearly two weeks because heavy spring snowpack kept these high-elevation environments snow-covered into July.

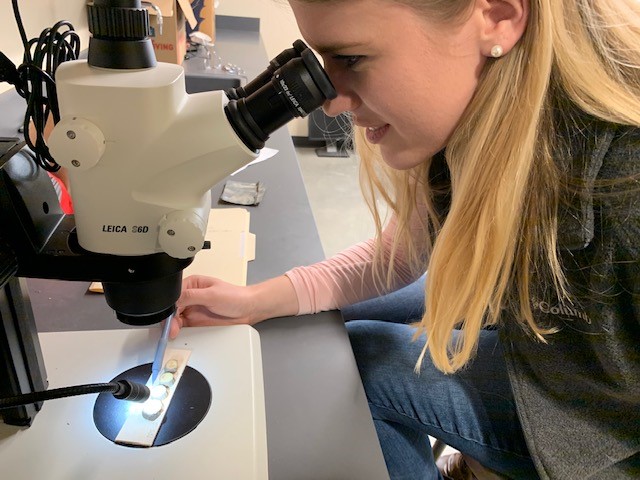

Professor Clayton Blodgett joined the field crew to help at their Santa Fe-area site, and Cyd Smith, an undergraduate student, is helping in the lab to process samples in preparation for dating them under a microscope.