But What about the Bedouins?

But what do the Bedouins think about all this change, after 10,000 years of pride in their ways?

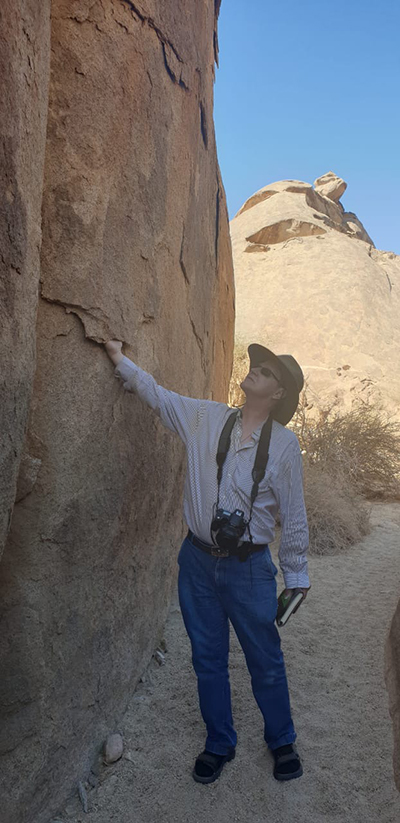

Hobbs, who has visited more than 100 countries, used to lead tours around the world, and realizes it’s very rare to have contact with indigenous peoples, as well as get insight into their unique knowledge. So his aim with the Bedouin is to find out what they want, how they feel, what they will and won’t accept.

“We talked about their concerns regarding tourism,” Hobbs says. “I asked what are the things you think would be good or bad as far as tourism? They want to benefit from it, but at the same time, they want tourists to maintain a safe, respectable distance — especially from their homes.”

Their homes are black wool tents called bayts which are the property of women and are ideally suited to the desert. They are made from goat or sheep wool, and have different sections for various purposes. For example, when men from outside the family come and want to converse, women and children leave the main area of the tent. The men go to the male area where they talk starting with rounds of coffee, tea, and dates. The women go another side of the tent called the hareem so their privacy can be respected.

Women and children take care of the livestock, mainly sheep and goats, walking them to where there is plant life and fodder available for them to eat. The men tend to the camels, which are highly valued and expensive animals. “They don’t want tourists to just randomly come out there disturbing their quality of life and their livestock and [belongings],” Hobbs says.

The women also have traditionally made lots of beautiful handicrafts that are part of their material culture and that they could sell through cooperatives to tourists, he adds. “There are definitely things that Bedouin women can do in the tourism economy. But they’ll have minimal contact with foreign tourists.”

The main benefits for the Bedouin from tourist development are economic opportunities, such as selling crafts, working as guides, trackers or falconers, telling lore and epic verbal poetry with the help of bilingual guides, and having preference in hiring opportunities within the development projects — such as trail makers, construction workers, drivers, mechanics, and much more.

“They want to have first place in that hiring process,” says Hobbs. “So far, the Kingdom has promised local peoples that will happen. You don’t want to bring in foreign workers if you can employ local workers. That’s part of Vision 2030 and what they call “Saudization” — to try to take jobs that normally would be filled by foreign workers and instead have Saudis do them.

“So economic opportunities would be the first thing the Bedouin look at. And I’d say number two and three would also relate to that kind of broad category of economic welfare.”

Another project area Hobbs might work in is helping the Bedouin reintroduce animals to their historical ranges where they have been hunted out, such as ostriches, leopards, ibex [wild goats], and gazelles [wild antelopes] “So those will be restored ecosystems when they reintroduce those animals, where tourists can see the wildlife adjusting to habitats over time.” Wildlife restoration is something the Bedouin have requested.

So Why Hobbs?

Hobbs was introduced to the Bedouin for the first time when he was 10 years old living in Saudi Arabia with his family. His father, a general manager/engineer, worked for a company that maintained the airport at Dhahran, which serves the oil-producing area of Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province.

One of his Dad’s friends, a fire chief, invited Hobbs to go out into the desert of northern Saudi Arabia, to look for dhabbs, large burrowing lizards. “I’m a real reptile freak,” Hobbs says.

So, they took off in Chief Hans’ little open-air vehicle, but while enjoying the desert all day they got lost and disorientated after nightfall and couldn’t find their way back to the main road. But luckily they did happen upon a Bedouin family, who were in the desert with their wool tent and their sheep, goats, and camels.

“They fed and watered us, gave us coffee and tea and dates, and made sure we were warm in that cold nighttime air, and then got us back on the highway. We got home late the next morning to learn that my parents were deeply distressed and had sent a search party.

“But thanks to the Bedouin, nothing bad happened to us. I had a really early encounter that left a very favorable impression on me about these people.”

While a junior at the University of California-Santa Cruz he studied abroad in Egypt [1976-1977]. “That’s when I fell in love with Egypt,” he says. “And I was to develop two great interests there. There was a while there that I was really sure I was going to be an Egyptologist. I spent so much time in the tombs and the temples and museums, just fascinated by ancient Egypt. Then I started meeting Egyptologists and found the work they did to be terribly boring, so I’m actually glad I did not go in that direction. I learned Arabic and that let me learn about a fascinating modern Egypt -- but modern Egypt with a lifestyle that goes back 10,000 years with the Bedouin.”

Hobbs’ next encounter with the Egyptian Bedouin was in Egypt in 1980 when he was studying Arabic for a year and doing research on bird migration. He had just received a fully-funded award from Center for Arabic Study Abroad [CASA].

But the Arabic he learned was a mix of classical and Egyptian Arabic, understood by the Bedouin, but kind of a “city slicker” Arabic, he says.

“Their [the desert Bedouin's] vocabulary is 80 percent about rocks and animals and skies and birds and insects and water and tents and camels and places and people,” Hobbs says. “So I had to learn all that vocabulary from them. That took a while. At first I was totally disoriented, even though I was theoretically fluent in Arabic.”

But soon a great opportunity arrived.

“Looking for migrating white storks in the Eastern Desert, I met the Ma’aza Bedouin people and one man in particular, Saleh Ali, who became my mentor and guide. I was in my early 20s and didn’t know what I was going to do for the rest of my life, but a few months later after we climbed Egypt’s highest mountain — we were up there on the summit — I asked him ‘Hey Saleh, what would you think if I came back and spent a year or two with you and your people, and he said ‘ahhh come back, come back.’

“That’s when I decided I needed to get a Ph.D. as a way to spend that time with Saleh’s people. I went back to the University of Texas and enrolled in the doctoral program in geography. For my dissertation research I spent a couple of years with these people out in the desert just learning everything I could about their knowledge and uses of their desert wilderness.

“It’s kind of old school geography, but it’s also ethnography. Basically, I did anthropological work interviewing all these people all of the time, but in an open-ended way, you know, not structured -- about their lives and their interests and their knowledge. That became my dissertation and my first book [Bedouin Life in the Egyptian Wilderness], and then I went back and did a lot of field work after that.”

He says Saleh, who passed away in 2015, taught him everything he knows, constantly coaching him on vocabulary and customs. “I listened and learned everything I could,” he says. “There wasn’t any subject I wasn’t interested in. And everything they talked about I recorded and transcribed. At nighttime, when they went to bed, I rewound my little microcassettes and put it all down in journal, handwritten form. Then I’d go back to Cairo and type it up. I didn’t have a computer. I’d go out about 40 days at a time, take a break, process my notes in Cairo, and then go back to the field.”

He and Saleh and other companions got their supplies in the Red Sea town of Hughada before each trip. While in the field he did what they did, and slept under the stars because they don’t use tents, and helped where needed. “But Saleh always had secret destinations he’d break out as we travelled, and these were the most interesting – like a cave filled with the dried-out, preserved bodies of leopards and ibex carbon-dated as much as 7,500 years ago.

“I did a lot of research after I arrived at MU on these people and their environments,” he says. “Both in Eastern Desert between the Nile and the Red Sea and in the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt."

He says some Bedouin tribes of Egypt, including the Ma’aza, are descendants of people who migrated from the region where he is currently working in Saudi Arabia, a migration that happened about 300 years ago.

“They mostly walked overland with their livestock and settled in Egypt and they still have kinfolk on both sides of the Red Sea.” Both the Ma’aza of Egypt and Arabia speak the same dialect, with few variations.

He also had team leader experience working with the Bedouin in a project he helped on in the late 1990s in the Sinai. The project, funded by the European Union, was to create the St. Katherine National Park. Its huge area is home to many Bedouin.

“My role was to find ways that the local Bedouin living inside the park, which belonged to seven different tribes could, from the very get-go, help influence our decision-making about establishing the park. Also, we could help them with ways of earning a living and contributing their indigenous knowledge, which is really deep: how they know the land and all the resources. They know the environment so well.

“It was a symbiotic relationship we created in setting up the St. Katherine National Park between the Bedouin and the park itself, the park management.”

In his current work he is taking the same principle into the field in Saudi Arabia. He worked there twice this fall, and will be ready to go again when coronavirus and the oil markets allow.

Why the Bedouin

When asked what attracts him most to the Bedouin peoples of Egypt and Saudi Arabia, Hobbs is quick to answer:

“Their knowledge, their insight, their wisdom, their depth and breadth of experience with nature in a wilderness setting. Their honesty! I have never met anybody who told me a lie or tried to deceive me in any way. Their strength, their endurance. To live out in the wilderness is really a taxing thing to do. It’s not an easy life, but I love their sense of freedom, and that’s something they talk about all the time, that huriya, freedom, they have freedom. And to look through their eyes at people who live in villages and cities — they’re all sort of prisoners of their own homes.

He remembers going into town with his Bedouin friends to get supplies and seeing them get visibly uncomfortable. “They didn’t want to be there more than necessary,” Hobbs says. “They’d come and go in the same day, instead of spending the night. So, you know, freedom under desert skies is very important to them.

“And their faith. They are all very devout Muslims but they never really question me or challenge me about my faith. I just haven’t met a finer group of people anywhere I my life. And I’ve been to a lot of places.”

Could Freedom Be Compromised?

But will these resorts impact their freedoms?

“It could, it could,” says Hobbs. “That’s definitely one of the dangers. There are areas that will become no-go for the Bedouin. If the Bedouin don’t bring their livestock within three kilometers, a mile and a half perimeter from the resort, I think that’s actually a good thing. It will be good for both parties.

“That way men and women can dress the way they want as tourists when they are in the resort, and when they go out they can dress up for the field. I think there will be those kinds of boundaries.

“But one of the issues that came up was if the Bedouin would have to be relocated because of this project, the hotels and such. And they are very afraid about that. When I was there last fall, they asked me, ‘what’s going to happen to us?’ and ‘Are we going to be moved from our traditional lands?’”

Hobbs was assured by Saudi government officials that was not going to be the case. They would not be forced out of their homelands, but possibly in one or two isolated cases: a single household or two households would be bought out and asked to move elsewhere, but they’d be compensated for that.

“So that’s part of the work I did, too,” Hobbs says. “Was to try to build in those assurances and guarantees that their life wouldn’t be impacted so hard.”

He says the Bedouin are excited and nervous, just like everyone else in Saudi Arabia. The country is in a state of change. No one can tell fully what is in their future. “But I didn’t meet Bedouin who said, ‘go away, go away. We don’t want to hear anything about this,” Hobbs says.

“Before I left on the second visit, I wrote recommendations and at the top of the list is that anybody from the company who goes out into the traditional tribal areas needs to call this phone number of the sheikh, the head man of the tribe who lives in a village along the coast and as a courtesy say, today or tomorrow or in two days, we are going to be in such and such an area doing our surveys for whatever they are doing with the project. It’s just common courtesy and it will prevent the kinds of clashes that would otherwise come up.”

And as for Hobbs, working with the Bedouin is his journey, his passion, what makes him happy. “I’ve been teaching at MU for more than 30 years and all my students learned about the Bedouin,” he says. “The stuff I did in the deserts and elsewhere in the Middle East. Teaching Geography of the Middle East is always a joy to me because a lot of it is personal accounts, photos, and videos of not only those people, but of historic things I witnessed, like when the Shah of Iran died -- I was taking pictures in the funeral procession through Cairo. I was there right before and right after Sadat was assassinated in 1981. And I went up to Lebanon during the Civil War of the ‘70s and learned how awful war is. I’ve met Palestinians and Israelis and teach their conflict from both perspectives. I’ve worked and lived and visited a lot of places in the Middle East, and shared experiences there with my wife Cindy and my Mom and other family members. I’ve done consulting in the United Arab Emirates on environmental planning and given papers just like all professors do at conferences — many in the Middle East and about the Middle East. That’s my main research area.

“And I owe it all to Saleh.”

Saleh was more than his mentor and guide. He was a friend he will remember always. In his article titled "MyBedouinWay-Fellow," published in Arab World Geographer in 2016, he wrote:

"What was Saleh like? Charismatic, for starters. Saleh was knowledgeable, and his own people sought him out for information. He was witty, humble, inventive, and loyal. He used his signature belly-laugh a lot, and he was funny: there was the “Mister Mustache” Saleh who wore sprigs of wormwood between his upper lip and his nose; the “Mister Lizard Face” Saleh who sported a fringe-toed lizard on his cheek; and then there was the time he placed a two-foot long adult dhabb (Uromastyx) lizard on top of his head and asked “Do you like my hat?” I cannot remember him angry, except when Subhi ‘Awad cut down and charcoaled a great acacia tree in Wadi Naggat. That was taboo.

"Saleh was generous. He practiced the hospitality Bedouin are famous for, but his kindness went far beyond that. He did not have to do anything for me. He could have said he was busy, instead of giving me 40 days of his life at a stretch ....

"Looking back, I wonder how much I offered Saleh. Certainly not much money – I gave him a nominal “tip” at the end of each trip. Nothing other than friendship can explain it."